The Gold Rush of La Panza

Lorie A. Woodward April 10, 2019 (with some additions!)

La Panza, now a ghost town located

in the La Panza mountain range in San Luis Obispo County, was once the site of

California’s only Coast Range gold rush. (4

miles on Pozo Road south of Hwy 58)

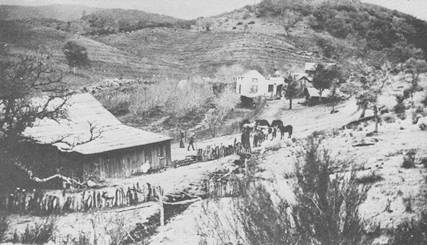

La Panza post office and store - 1892

The name La Panza can be traced back

to the early days of Spanish and Mexican settlement when the area was known as

prime territory for Ursus horribilis,

the now-extinct California grizzly bear. Vaqueros intent on protecting their

livestock often used bits of slaughtered cattle, including “the paunch,” to

lure bears, so they could be poisoned, trapped or lassoed.

Some of the bears may have been

caught and kept alive. In the late 19th century in frontier California,

promoters pitted captured bears against full-grown bulls in a public fight to

the death. The last captive California

Grizzly was caught in 1889 and lived 22 years in captivity. Allen Kelly had to bring

William Randolph Hearst a live grizzly to win his bet!

While California’s legendary Gold

Rush took place from 1848–1855, the La Panza gold rush made its historical mark

beginning in 1878. According to the accepted mix of legend, lore and fact, a

failed mule deer hunt led to the discovery of gold.

Needing to refill his larder, Efranio

Trujillo mounted his horse and left his camp in search of a deer. A day of hard

riding finally brought him success in the form of a young buck with barely

emerged antlers. When Trujillo fired, he wounded the animal, which bounded

away.

Trujillo trailed the injured animal

until he lost the tracks and realized the animal’s wound wasn’t life

threatening. Disgruntled he stopped at a spring to rest his horse and

belatedly eat his lunch. As he bent toward the refreshing water, he saw a

glittering sandbar. In that mixture of sand and precious metal, Trujillo

spotted gold flakes, two or three of which were large enough to pick up by hand.

Strictly speaking, though,

Trujillo’s discovery was no discovery at all. The mission padres had known of

gold in the La Panza hills and had Native American neophytes likely from the

Chumash tribe mining there in the early 1800s. In the 1830s when secularization

of the missions had taken over Church property in California, the padres had

closed the mines and sworn the Native Americans to secrecy.

No one swore Trujillo to secrecy,

and as word of the “flakes big enough to pick up by hand” spread, the once

isolated tributary of the San Juan River boomed and a boisterous mining camp

was formed, complete with a saloon and dance hall. Within the next few weeks,

between 500 and 600 men stampeded into the area hoping to strike it rich. The

area would become one of the most important California gold fields outside the

Mother Lode country.

In the spring of 1879, word of the

mining excitement reached Dr. Thomas C. Still, a medical practitioner from Kern

County. He moved his family to the mining field. Still not only hauled and sold

produce to the mining camp, he established a general store and applied for a

post office permit. In November of that year, the La Panza Post Office was

established.

The post office was named after the

nearby La Panza Ranch, which had been owned in the 1860s by Drury James, uncle

of outlaws Frank and Jesse. According to stories, the duo, under false names,

holed up at the ranch for a time. Their ruse didn’t fool the locals.

By the time gold fever hit the area,

the ranch, which was adjacent to the gold field, had been sold to the

partnership of Jones and Schoenfeld. They raised sheep and cattle.

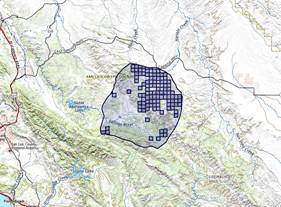

La

Panza – eastern side of the La Panza Range La Panza Mining District

Mining camps, with their mix of

prospectors, drifters, grifters and outlaws, were a cauldron for mayhem.

Fortunately for area residents, Dr. Still continued to practice medicine. Many

decades later, Still’s grandson, O.M. Maclean, relayed one of the many episodes

of frontier medicine.

One night Dr. Still was roused from

his sleep by urgent, incessant knocking. When he opened the door, a man asked

him to come treat a wounded friend. In answer to the question of what happened,

the excited man blurted out, “I shot a man.” He caught his error and quickly said,

“I mean, a man has shot himself.” Upon arriving at the wounded man’s bedside,

the doctor determined the patient was in very grave condition. Despite his

patient’s precarious hold on life, Dr. Still successfully removed the bullet.

He instructed the patient’s friend that moving the injured man could prove

fatal. The next morning Dr. Still was greeted by an empty room. The two men, on

the run from the law, had disappeared because they were afraid he would report

the incident to the sheriff.

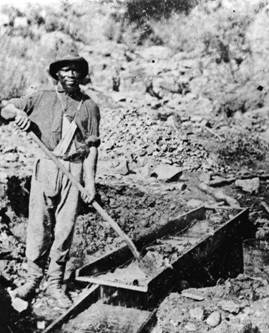

While La Panza generated a lot of

excitement, it was not an easy field to work. Many of the streams were small

and intermittent. An anonymous miner who prospected in the area published an

account in the South Coast newspaper on February 5, 1879. He wrote: “Prospects

of fine gold are found nearly everywhere in the streams. Evidently there are

rich pockets of gold which wash into the streams and lower flats, but there is

not enough water to use the hydraulic process.”

The first official report of gold

production was made in 1882 when $5,000 was reportedly taken out. By 1886, the

region was producing $9,164 a year, which proved to be its largest recorded

annual take, but it dropped to $1,740 in 1887. The numbers continued to rise

and fall each year, with the lowest annual recovery of $124 occurring in 1913,

the last available report.

While there was never a huge strike,

it is estimated the La Panza region produced at least $100,000 worth of the

precious metal. In comparison, the Sacramento Valley, which is home to Sutter’s

Mill and the ensuing Mother Lode strikes, produced more than $2 billion worth

of gold from 1848–1852.

As gold production subsided, so did

gold fever and the area’s population. Quiet returned to the region as did deer,

mountain lions, coyotes and ranching.

*Exploitation and Enslavement of Indigenous

People in California

Enslavement in one

form or another (and some say genocide) began with the Franciscan missions. Indians

continued to suffer under Mexican and American rule. Usually they labored in

farming and ranching. Gold had been discovered around the 1830s in La Panza and

kept a secret by the fathers while Indians did the mining and kept their

secret. Thanks

to other laws passed in the early 1850s, which barred Indigenous people not

only from voting but from serving as jurors, judges, or witnesses in criminal

cases, white people were free to push the boundaries of the state’s

apprenticeship laws to the cruelest possible outcomes. These anti-Indian laws “amounted to a virtual grant of

impunity to those who would attack them or commit crimes against them or

grossly exploit them,” says Benjamin Madley, a professor of history at UCLA and

the author of An American Genocide: The United States and

the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873.

Indian revolt in

1775, San Diego Mission Indians

burn San Luis Obispo Mission 3 times

Revolt and Defiance are evidence of the racism and

brutality of the ‘White Man’s Rule’.

* The Anti-Coolie Act of 1862 was blatantly anti-Chinese which

‘taxed’ the workers when their weekly wage might be $3 to $4. They were

economically a threat to the white settlers. Eight years later, the Naturalization

Act of 1870 allowed Africans to become citizens through naturalization, while

continuing to exclude Asians. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion

Act, which more directly restricted Chinese immigration and naturalization.

*Black Slavery continues. The framers of California’s 1849 state constitution wrote into law the systematic denial of suffrage and other civil rights to non-white citizens. Slavery did persist in California even without legal authority. Some slaveowners simply refused to notify their slaves of the prohibition, and continued to trade slaves within the state. California banned slavery but also attempted to remove all free blacks.

SLO Outlaws Colored Miners

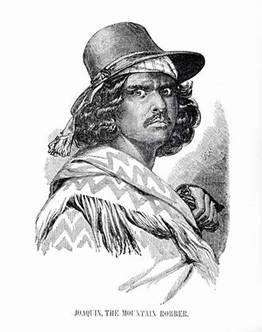

Joaquin Murrieta – Outlaw

* The legend of the people’s outlaw, Joaquin Murrieta, is

evidence of the racism against the Hispanics in early California. As a young

Mexican, he was subject to a litany of racist injustices shortly after entering

the country: tied up and whipped, then made to watch his wife gang-raped and

his brother hung from a tree after a crowd of white people falsely accused him

of stealing a horse. Vowing revenge, Murrieta turned to a life of banditry,

stealing from Anglo Americans until he was tracked down by law enforcement and beheaded.